SUMMARY: Dealing With Corruption

- Corruption is common in everyday travel situations

- You will not change the system on the road

- Stay calm, polite and non-confrontational

- Know your documents and your legal position

- Avoid escalation – time and patience are leverage

- Decide pragmatically when to stand firm and when to move on

- Personal safety always comes first

From Confrontation to Pragmatism

On this planet there are roughly 30 different personality types – better described as models.

Every human being is a unique mix of genetics, biography and context. No two are identical.

As a result, people act according to their character traits: often similar, rarely identical, usually intuitive – and when it comes to dealing with corruption: very often wrong.

Let’s start with us — Fenny and me.

Fenny is calm, relaxed and composed. She rarely gets genuinely angry, instinctively tries to de-escalate and saves her energy for what actually matters. She connects with people on an emotional level.

I – Totti – am very different. I’m not particularly easy to deal with, when things are pushed too far. In my professional past, the rule was simple: survive.

Everyone was trying to take advantage of you. Over the last forty years I built a thick skin, was often undiplomatic and frequently arrogant – because frankly – arrogance can get you surprisingly far and brought me, where I am now.

I can argue well, but I can also over-argue, derail discussions or destroy them entirely.

I rarely avoided confrontation, usually with my finger pointed firmly in the air.

My legal insurance was busy – courtrooms were familiar territory. And I won. Always.

Head-through-the-wall mentality :

“I’m right and you can fuck off”

Pretty much the worst set of character traits, when it comes to dealing with corruption!

But I learned. Age does that – if you let it.

Today it’s about energy and efficiency. I’m far less willing to engage in confrontation and instead look for pragmatic and – above all – fast solutions. Still, common sense sometimes trips me up and I fall back into old habits.

When it comes to corrupt situations, this is where I learned the most.

I developed my own way of communicating – a specific rhetoric that now works well in the vast majority of cases.

That said: no matter how calm, polite or friendly I am – push it too far and Pandora’s Box opens quickly.

Not everyone is good at talking. Not everyone has confident body language. Some appear introverted, reserved, shy or insecure. These people become – and there is no polite way to put this – easy targets for those trying to exploit them.

This guide shows how you never, ever need to pay money for something that does not exist, is not legitimate and therefore simply illegal. One thing is crucial to understand: not only the corrupt official commits a crime –

You Are Commiting Crime As Well!

Understanding Borders, Checkpoints and Corruption

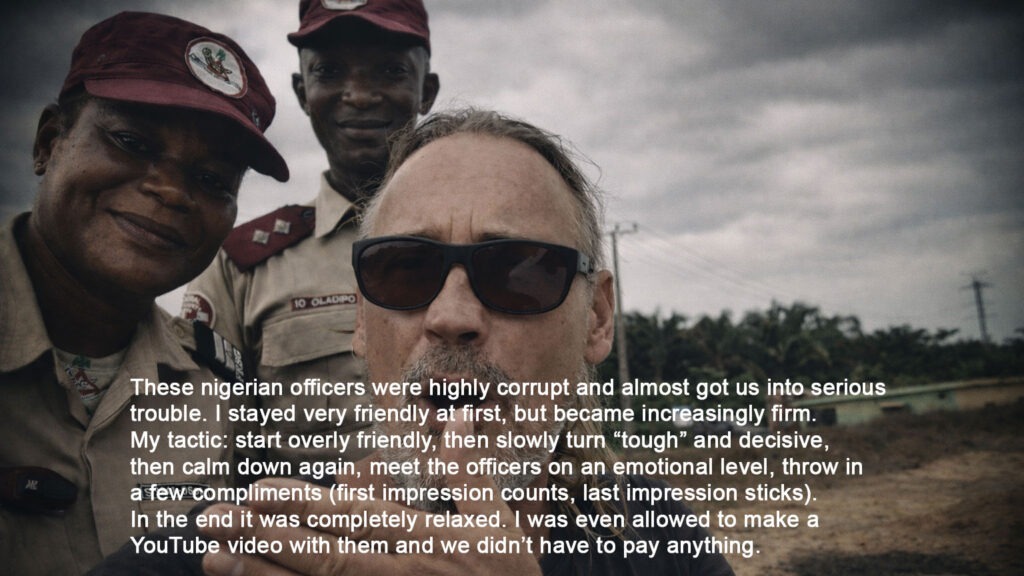

We’ve lost count of how many borders we’ve crossed over the last thirty years, how many checkpoints we’ve passed and how many police officers we’ve encountered – and, quite often, pushed back against. In Nigeria alone we dealt with 202 checkpoints and several hundred officers. Most of them were ultra-cool, super friendly, but also: corrupt- nearly every-single-one!

Every border crossing and every officer comes with their own challenges and requires a different approach.

To handle this properly, you need to understand three things:

a) what corruption actually is,

b) where it comes from and

c) how officers think and operate.

Once you understand that, you build your strategies around it.

Three Levels of Corruption

Corruption comes in different forms and levels. Not every encounter is about money and not every officer operates the same way. There is a clear difference between informal expectations, subtle pressure and outright demands.

Sometimes corruption appears as vague hints, unnecessary delays or invented problems that suddenly require a “solution.” In other cases it is direct and blunt: pay or you do not move on. The level often depends on location, hierarchy, visibility and how much leverage an officer believes they have.

Low-level corruption is usually opportunistic and transactional. It relies on impatience, uncertainty and fear of consequences. Higher-level corruption is more structured, more confident and often protected by authority or distance from public scrutiny.

Understanding these differences matters. Responding to a subtle hint as if it were an open demand, can escalate a situation unnecessarily. Treating a clear demand as a misunderstanding, can sometimes defuse it.

The key is observation: tone, body language, setting and timing tell you more than words ever will.

These different levels often show up very clearly.

Level 1 – Indirect and informal

This is the most common and often the least aggressive form. It sounds harmless and is usually framed as a favor or a joke: “What do you have for me?” or “Do you have something to eat?”

The intention is to test your reaction. Nothing is demanded openly. If ignored or handled calmly, it often goes nowhere.

Rule of thumb: give them nothing, no matter how friendly the request may sound. Any attempt, any gift, can be interpreted by others as a bribe.

Kindly decline, smile and add a friendly wink – the kind that signals respect, not mockery:

“I’m sorry, I’m not allowed to give anything. You know the rules better than I do – as a professional and respected officer.”Or, if they ask for a gift, reply with a smile:

“I brought you a (German) smile.”

Laugh lightly and keep the tone warm.

Level 2 – Direct but still personal

Here the tone changes. The request becomes explicit and personal, often mixed with assumptions or pressure:

“Give me your money, you are rich.”

At this stage the officer is no longer fishing – he is asking. The situation is still reversible, but boundaries matter.

Rule of thumb: if you are asked directly for money, respond calmly and keep it light:

“Why would I give you my money, sir?”

Laugh gently – not mockingly! – and add:

“I’m just glad I managed to scrape together enough to visit your beautiful country.”

Stay friendly and humorous, but make it clear through your body language that there is nothing to be gained from you – not now, not later.

Level 3 – Coercive and definitely illegal

This is no longer subtle and no longer negotiable in tone. Authority is used as leverage:

“You will not get your passports back unless you pay.”

At this level, the situation has crossed from opportunism into outright extortion. How you respond now has legal and safety implications.

Rule of thumb: If for instance documents are withheld or payment is demanded, your reaction becomes decisive. Stay calm and confident – you are in the right.

Respond evenly:

“That surprises me. I’m not aware that I need to pay money ,to get documents back, that belong to the German state.”If they do not back down, remain unhurried and composed:

“I have all the time in the world. Let’s have a coffee while you consider what should happen with the documents.”As a final step – if drinking a coffee doesn’t help – keep your tone respectful and controlled:

“Respected Sir, I feel this is going in the wrong direction. If our documents are not returned… I’m sorry, what was your name again?… I’m happy to contact the tourism office, the anti-corruption hotline, or my embassy, just to verify that I’m not doing anything illegal or unlawfully refusing to comply.”Then add calmly:

“I’m appealing to your professionalism, because I can see that otherwise you are doing your job very well.”

Important note!

Level-3 strategies are always situational. Visibility, time of day, location and the overall environment matter. What works at a public checkpoint during daylight, may be inappropriate in a remote area at night.

Use judgment. De-escalation and personal safety always come first.

Author’s note:

When a situation like this happened to me in Guinea, it escalated to the point, where I calmly held out my hands and said: “Then you’d better put handcuffs on me, arrest me and take me before a judge.”

The officer was visibly taken aback – and eventually let us go. USD 120 saved.

Understanding the Roots of Corruption

Not every corrupt officer is, by definition, a bad person. With a bit of empathy, it’s often possible to understand the situations: many of them are in low wages, irregular pay, family pressure, institutional decay and a system that quietly tolerates or even expects informal income.

In many places, corruption is not an exception, but a parallel system. It fills gaps left by weak institutions, poor enforcement and unclear accountability. For some, it becomes normalized behavior – learned early, reinforced daily and rarely challenged.

Understanding this context helps explain behavior, but it does not justify it. Empathy is not approval. Personal hardship does not legitimize abusing authority or shifting responsibility onto others.

There is a clear line between understanding why something happens and accepting it as normal.

Becoming corrupt out of personal hardship

does not legitimize an illegal act.

The Psychology on Both Sides

Encounters at borders and checkpoints are not primarily legal or administrative situations – they are human interactions. Two sides meet, each with their own expectations, pressure and instincts.

Travelers often arrive tired, tense or defensive, focused on rules and documents. Officers, on the other hand, seem to sense from a distance who is behind the wheel – almost as if they can smell the mindset of the person approaching. Confidence, insecurity, impatience or calmness are often read long before a single word is spoken.

Both sides react intuitively, often within seconds. Understanding this shared psychology matters. Many situations escalate or dissolve not because of law or authority, but because of tone, body language and perceived intent. Recognizing how both sides think – and how reactions influence each other – is key to navigating these encounters calmly and effectively.

The Psychological Perspective of Officers

Many interactions at checkpoints follow a simple psychological script. Officers constantly read people. Not documents first – people. Tone, facial expression, body language and reaction speed matter more than what is actually said.

If they sense tension, fear, irritation or hostility – no smile, no eye contact, a short or rude tone – the situation often tightens. What was routine suddenly becomes a “problem.” More questions appear, procedures slow down and authority is asserted more forcefully. Resistance, even passive resistance, is interpreted as disrespect or challenge.

If, on the other hand, they see people who wave, smile, greet them openly and appear relaxed, the dynamic often changes immediately. Friendly behavior signals: no threat, no confrontation, no drama. It lowers the perceived risk and removes the need to assert dominance.

Humor plays a key role. A light joke, a warm smile or an easy laugh humanizes the interaction. It shifts the encounter from control to conversation. Not because officers are naive – but because the situation no longer feels adversarial.

Officers are also sensitive to confidence. Calm, relaxed confidence without arrogance signals experience. It suggests that the traveler knows the routine, is not afraid and is unlikely to be pressured easily. This often leads to quicker resolutions and fewer attempts to escalate.

In short, officers respond less to what you say than to how you make them feel. Friendly, relaxed behavior reduces friction. Tension, defensiveness or rudeness increase it.

Understanding this psychology does not guarantee success, but it explains why some encounters dissolve within seconds, while others spiral into unnecessary conflict.

Friendliness and kindness are always the key.

And a smile disarms – every time.

The Traveler’s Psychology: Intent and Control

Our aim is to retain control from the outset by shaping the interaction early – using distraction, conversational redirection and deliberate engagement through friendliness and humor. Rhetoric and dialectical skill matter, because whoever defines the tone and structure of the exchange, often defines its outcome.

From our side, friendliness is intentional and sometimes deliberately amplified. Not fake and submissive, but proactive. We start talking immediately. An enthusiastic greeting, genuine appreciation for the country, how happy we are to finally be here. This shifts the dynamic instantly.

It distracts and breaks the expected script. Suddenly, the officer is reacting instead of leading.

Posture matters. Chest forward, upright stance. A calm, deep and friendly voice. Open, confident, without hesitation or fear. The message is clear: we are comfortable, we are experienced and we are in control of ourselves (and of the current situation). We lead the interaction and subtly guide where it goes.

If I need to step out of the vehicle, I do so confidently. Upright posture, a handshake if appropriate:

“Nice to meet you. How can I help you?”

We deliberately work with words, body language, humor and emotion.

Sometimes it’s as simple as saying: “Look, I’m getting goosebumps just thinking about the fact that my wife, my car and I made it all the way here – to your beautiful country.”

In many cases, this approach disarms the situation almost immediately. Very often, it never escalates beyond “Level 1”. High-level corruption attempts simply don’t happen.

There is, however, another type: the aggressive officer. Friendly behavior has no effect. The goal here is provocation in pushing you until you lose control and make a mistake.

In these moments, composure is everything. Breathe. Do NOT get angry.

Because “the best statement is the one delivered without anger”.

We prepare mentally for these situations, especially when we know what kind of border or checkpoint lies ahead. I rehearse phrases, sentence fragments and remind myself to stay confident and grounded.

Authenticity, honesty, self-confidence and experience must be visible. Good posture. Clear speech. Respect the officer as a person of authority – regardless of his rank. Never accuse an officer of corruption. Never corner them into a position they cannot exit. Always leave them an exit strategy.

The underlying message is simple and unspoken: I travel long-term. I know how this works. Let’s keep this easy.

That combination – controlled friendliness, confidence and psychological awareness – is often more effective than any argument or document.

If none of this works, we wait it out. We stay calm, remain friendly and never (well… I should say “barely”) become irritated or loud. By doing so, we signal that we have time, patience and enough experience to see the situation through.

If an officer crosses the line, I set boundaries immediately and without detours. I state clearly how this interaction needs to proceed, while explicitly expressing respect for the officer as a person. I make it clear that the situation is drifting out of control.

My voice becomes firmer – still calm and respectful, but noticeably more authoritative than before. This is the officer’s final opportunity to step back before the situation escalates further and is going to open Pandoras Box.

As a final step, I sometimes use a psychological – and not entirely risk-free – approach. I make it clear that I will not pay, no matter what. I explicitly offer myself for arrest and state, that I am willing to be taken before a judge, regardless of how long it takes.

The message is unambiguous: this is the line. No further.

At this point, the officer needs an exit strategy. He has to act, but without losing face. I deliberately lower the tension again, return to a friendly tone and subtle offer a way out, that allows him to disengage without embarrassment.

This is difficult to describe in abstract terms, but at the end of this article, I provide concrete examples of how such exit paths can look in practice.

In the end, we always managed to get out, even when situations escalated and carried real risk.

When Not to Push Further

There are moments when psychology, confidence and patience stop being tools and start becoming risks. Knowing where that line is, matters more than any tactic.

We do not push further at night, in isolated areas or when there are no witnesses. We do not push when alcohol is involved or when the atmosphere turns unpredictable. And we do not sit things out when weapons come into play or when the balance of power is clearly no longer stable.

In those situations, the priority shifts. Safety comes before principle. Getting out clean matters more than being right. Walking away with your freedom intact is always the better outcome.

This is not weakness but sound judgment.

A Legal Reality Check

In real overland travel, corruption patterns vary greatly by region – like we documented in detail during our West Africa journey.

What you’re reading here isn’t meant as instructions or a handbook. It’s simply what we’ve learned over decades on the road – what worked for us, what didn’t and what we adjusted along the way.

Laws change from country to country, authority is interpreted differently and local realities often outweigh whatever is written down in regulations. Every situation is its own mix of people, place and timing. In the end, each traveler has to make their own decisions and live with the consequences.

This is not legal advice. It’s our very experience from the field, nothing more… nothing less.

But hey, let’s be honest – At the end of the day, it’s like this:

The officer at the boom gate is a small cog in the system, someone who rarely has real authority.

They demand respect and often make themselves more important than they actually are. Many of those we encountered, couldn’t even read or write (though to be clear: some absolutely can).

That said, they also have something to lose: their job.

That’s why many act very subtly and – because they’re clever – operate right at the edge of legality, but still on their side of the line.

Others, however, are blunt and rigid and seem to give little thought to the consequences, their actions might have for themselves.

I’m convinced, that as long as you’re not traveling in a country where no law applies at all (what I would call lawless states), travelers are – despite appearances – generally on the safer side and initially have little to fear. In the end, many countries depend on travelers and hardly any country wants a public incident once a traveler starts asserting their rights.

Even in Afghanistan, in February 2026, a corrupt official was arrested by the Taliban after being exposed, because travelers contacted the appropriate authorities. At many border posts, there are notices with phone numbers for “corruption hotlines.” We often subtly draw the attention of potentially corrupt officers to these signs or posters.

As travelers, we usually have little more to lose than time and nerves.

The officer, however, risks his livelihood. That’s just it!

When you’re traveling, the moment you pay, changes everything.

The Cost of Giving In

The moment you give in, you signal that you’re an easy mark. Word travels fast in these circles. By the next checkpoint, you’re no longer just another traveler – you’re a walking ATM. The bar drops instantly. Requests come quicker, demands get pushier and whatever patience existed before is suddenly gone.

There’s also a psychological cost that shouldn’t be underestimated. Every time you pay under pressure, you train yourself to fold. Your confidence takes a hit. The calm, clear-headed way you once handled difficult situations slowly gets replaced by a reflex to simply make the problem disappear. Over time, you stop dealing with situations – you start avoiding them. Travel begins to feel smaller, not freer.

Then there’s the cold legal reality most people prefer to ignore. In many countries, handing over that “little something” is a crime – not only for the officer asking, but also for you paying. What feels like a quick fix in the moment, can later turn into fines, court appearances, deportation risks or permanent marks on your record.

Yes, refusing to pay can cost time, nerves and discomfort. Sometimes it means standing around longer than you’d like, in the heat, the rain or the dust.

But paying almost always, costs more in the long run: to your self-respect, to the travelers who come after you and to the entire corrupt system, that keeps repeating itself, simply because it works.

This isn’t about being a hero or taking the moral high ground.

It’s about understanding, what you’re really buying, when you quietly say, “Okay, fine,” and hand over the cash.

Do NOT do that!

Are there exceptions?

No. Not Really.

Even though, as experienced travelers, we have a lot of understanding for less experienced travelers – especially those traveling with dogs or small children – who may be tempted to pay a small amount to save time or avoid tense situations, it remains a criminal offense. And it can have serious consequences for the travelers themselves.

The only legitimate exception is immediate danger to life or serious physical harm.

If a situation escalates to real, credible threat and paying is the only way to de-escalate and get out safely, survival comes first.

Especially when traveling with children, responsibility, good preparation and clear decisions matter most.

Bribery is illegal in many jurisdictions and not “just a local workaround” – the OECD provides a concise overview of how foreign bribery is treated internationally.

In the end, none of this is really about being “right” or winning some moral argument.

It’s about keeping going… together.

Over time, you learn, where it’s worth digging in your heels and where it’s smarter to let something slide. You also learn humility along the way. We misread situations. We push too hard, say the wrong thing or freeze up. We mess up, feel stupid for a moment, learn from it and try to do better next time.

You’re never going to fix the broken systems you run into. What you can do is, learn how to move through them without losing your own compass and without turning into someone you don’t recognize.

Staying calm when everything feels off, staying kind even when you’re angry and knowing, when to shut up and walk away – those things matter far more than any clever line or power move.

We wish all of you the very best on your journey – whatever your path may look like in the end.

Safe travels… and maybe we’ll cross paths someday, somewhere on the road.

Yours,

Totti & Fenny

(Everything written here was originally written in German by Totti, translated into English and then refined by AI to improve clarity and readability – so that browsers can also translate it more accurately into other languages..)

FAQ - Some Examples and Tips Of How We dealt With Such Situations

How to prepare properly to avoid such situations?

Preparation significantly reduces risk and this is, what we learned very quickly:

Make copies of all documents. Passports, driver’s license, vehicle papers. Keep originals out of reach and hand over copies only. We let produce professional looking laminates of our passports, drivers licenses and other important documents.

Check iOverlander for current border reports, checkpoint patterns or other dangerous or suspicious areas, where corruption might occur.

Read recent Facebook group posts from travelers, who crossed the same borders or regions shortly before you.

Verify official requirements on government or embassy websites: required documents, fees, procedures and official prices.

Know the rules better than the officer.

If we read in a group, on a website or on platforms like iOverlander about corrupt border posts and their tactics, we always research the actual laws.

AI can be extremely helpful here – but always double-check.Print the relevant regulations, carry them with you and only show them if absolutely necessary.

Calm confidence comes from preparation.

Additional preparation points:

Always ask for a receipt and the officer’s name if it’s not clearly visible on the uniform. We openly write it down – you have the right to do so.

We always ask for the legal basis or – what police are supposed to have – a fee schedule.

At checkpoints, we never hand over cash directly to officers.

The only exception is an official authority (e.g. borders) where fees are posted, fixed and well known.If someone insists on cash, we calmly suggest doing it at the police headquarters or paying via bank transfer or bank deposit.

Our simple rule is: no transparency, no payment.

Last but not least – Dashcam

It’s also always a good idea to run a dashcam, as it records audio and video, as well as GPS data and time. Of course, this must be checked country by country, as the use of dashcams is not legal everywhere.

A (pot-bellied) officer asks you for something to eat or drink. Do you give him anything?

No. These days we don’t give anything anymore. I grin and say:

“Sorry, Sir, I can’t give you anything. We don’t do that anymore.”

And if he doesn’t let up:

“Take a look at my wife (36 kg). She truly needs food more than you do,”

and I grin and wink while pointing at his big beer belly.

You get stopped and they notice that the driver is wearing flip-flops. They want money from you.

Sure, they can want that – but I react like this, depending on the situation:

I look at him suspiciously and very politely ask whether he’s serious.

If he insists, I calmly suggest the following:

“Okay, Sir, let’s do it this way: I’ll get out my camping chair, the two of us sit down by the roadside and watch how many drivers—cars or motorbikes—are wearing flip-flops. If I’m the only one, you can show me the law and give me a receipt, and I’ll transfer the fine straight to a bank. No problem. I naturally respect your laws.”

An officer demands that you give him money. How do you react?

We had this happen. The officer went straight to the point as soon as I rolled down the window: “Give me your money, you are rich.”

I react laughing:

“Give me your gun, I don’t have one.”

Or a bit more firmly:

“Why should I give you my money? I need it myself.”

Or even more firmly:

“There is no way I’m giving you the money I worked hard for.”

And if none of that helps, I become very polite, lean toward him and whisper:

“Hey… you know I’m not allowed to give you anything. Otherwise I’d be committing bribery.”

And if he denies that, I say:

“You – and you know this very well – would be committing an offense too. That could cause you quite a lot of trouble,” (and I wink).

An officer checks the entire vehicle and it becomes obvious he wants money.

I let them search everything. No resistance.

If I’m asked whether I have a fire extinguisher, I reply like this:

“Yes, Sir. Two fire extinguishers, two reflective vests, three first-aid kits, two tow ropes, two tow hooks, and a shovel – because you never know who you might have to pull out of the shit. We’re always happy to help.”

If they then find something (it has happened before) – for example a broken license-plate light bulb – and demand 30 dollars instead of 5, I respond:

“Are you sure it’s 30 dollars? Absolutely sure?

Of course I follow your law. If you can show me the official fee schedule and give me a receipt, I’ll transfer the fine to a bank immediately.

But first, I’ll sit down by the roadside and take a look at how roadworthy the local vehicles are – then we can continue the discussion.”

Always calm. Friendly. Matter-of-fact. Confident.

A guy claims he’s a police officer, but he’s in civilian clothes and wants your passports. What do you do?

Yep. Happened more than once:

I stay calm and polite, but firm. I ask him to clearly identify himself and show an official police ID. No ID, no documents. NEVER! – simple as that.

I explain calmly:

“I’m happy to cooperate with uniformed police or officers who can properly identify themselves. But I don’t hand over passports to private individuals.”

If he insists, I suggest we go together to the nearest police station or checkpoint.

That usually ends the discussion very quickly.

Officers refuse to return your passports unless you pay a fee.

That happened before. Since then, we only hand over professional laminated copies (they look like the originals). When this happens, we stay relaxed and casual:

“Sir, these passports are the property of the Federal Republic of Germany. If you don’t return them, I’ll simply get new ones from the German embassy. That’s all. But I will certainly not pay.”

Then I stay calm and add:

“I think I’ll make myself a coffee and we’ll see how this develops.”

We sit it out, no matter how long it takes. Period!

What was the most absurd situation you’ve ever experienced?

Cameroon. We were stopped for allegedly “overtaking incorrectly.”

Traffic was chaotic and intense, but we hadn’t done anything wrong. Still, we were told to pay money – supposedly via a bank.

I asked what exactly our offense was and what about it was illegal.

Answer: “You did nothing illegal, but you still have to pay.”

I repeated the question several times.

Always the same answer: no offense, but payment required.

Completely absurd.

You can watch the whole situation on YouTube:

Westafrika Tour – CAMEROON – Episode 11

What was your most horrific situation?

A convoy in Cameroon (Ekok To Buea). We followed an unlit convoy until late in the evening.

We arrived. Trouble. Orders. Sleep.

At 2:30 a.m. (in Buea already), someone slammed a fist against our doors. Alarms screaming. A high-ranking officer (brigadier general) stood outside in casual clothes – one woman on his right, another on his left.

He demanded our IDs. We said we would only hand them over, if he identified himself first.

He started shouting and became super aggressive – and only then did we realize he was heavily drunk.

He rammed his elbow into my chest and physically blocked me from getting back into the van and closing the door. The situation escalated to a point where I became genuinely anxious and didn’t know how to react anymore. It caught me completely off guard.

I still did not hand over my IDs.

I misjudged the situation. This was the only case, where none of my strategies worked.

It left a trauma.

Have you ever gotten loud or even aggressive?

Ohhhh yes. More than once.

As I wrote at the beginning: I’m easy to deal with – as long as my intelligence isn’t chainsaw-raped and I’m not treated like an idiot.

Unfortunately, in situations like that I sometimes fail to control the adrenaline rush. From that moment on, it’s pure confrontation. I get very loud, sometimes I even shout down an entire border post and ask the officers whether they flushed their common sense down the toilet.

That said, I usually switch back quite quickly to my “very, very friendly” tactic – which, surprisingly, still works most of the time.

But: it’s not good.

The loud one always loses – unless he has an exit strategy, which I usually do.

Don’t you negotiate?

Yes – but it’s tactical.

If we’re stopped and someone tries to impose a fine, we argue our way out of it, until the officer starts lowering the amount. At that exact moment it becomes obvious, that this is corruption.

From then on, we go rigid and pay nothing – no matter how low he or she goes.

This happened to us in Guinea: he dropped from 120 USD to 20 USD.

How much more obvious can corruption get?

Where you able to film such situations?

Oh yes. You can see one clear example here in this blog post: Surviving Nigerian Checkpoints.

We also have many other videos, showing exactly these kinds of situations on YouTube.

But keep in mind: running a camera can also cause serious problems.

In many countries, filming is not permitted – or can even be a criminal offense.

We recorded covertly.

Have you ever paid a bribe?

No. We have never paid a bribe.

But we have fallen for fraudulent schemes often enough in the past – we simply didn’t know better.

Today, we’re far better prepared and can usually spot a corrupt situation immediately.

Danke für diesen außerordentlich guten Beitrag- hochinteressant und infirmativ!

Hey Conny… aber gerne doch und: vielen Dank 🙂